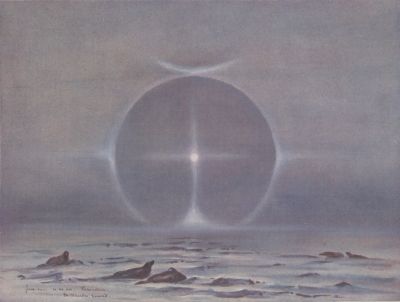

A Halo Round The Moon—E. A. Wilson, del.

With Panoramas, Maps, And Illustrations By The Late

Doctor Edward A. Wilson And Other Members Of The Expedition

| Page | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Contents | v | ||

| List of Illustrations | vii | ||

| List of Maps | viii | ||

| Chapter | VIII | Spring | 301 |

| Chapter | IX | The Polar Journey. I. The Barrier Stage | 317 |

| Chapter | X | The Polar Journey. II. The Beardmore Glacier | 350 |

| Chapter | XI | The Polar Journey. III. The Plateau To 87° 32´ S | 368 |

| Chapter | XII | The Polar Journey. IV. Returning Parties | 380 |

| Chapter | XIII | Suspense | 408 |

| Chapter | XIV | The Last Winter | 436 |

| Chapter | XV | Another Spring | 459 |

| Chapter | XVI | The Search Journey | 472 |

| Chapter | XVII | The Polar Journey. V. The Pole And After | 496 |

| Chapter | XVIII | The Polar Journey. VI. Farthest South | 527 |

| Chapter | XIX | Never Again | 543 |

| Glossary | 579 | ||

| Index | 581 |

| Page | ||

|---|---|---|

| A Halo round the Moon, showing vertical and horizontal shafts and mock Moons. | Frontispiece | |

| From a water-colour drawing by Dr. Edward A. Wilson. | ||

| Camp on the Barrier. November 22, 1911. A rough sketch for future use. | 322 | |

| From a sketch by Dr. Edward A. Wilson. | ||

| Parhelia. For description, see text. November 14, 1911. A rough sketch for future use. | 332 | |

| From a sketch by Dr. Edward A. Wilson. | ||

| Plate III. | The Mountains which lie between the Barrier and the Plateau as seen on December 1, 1911. | 338 |

| From sketches by Dr. Edward A. Wilson. | ||

| A Pony Camp on the Barrier. | 346 | |

| The Dog Teams leaving the Beardmore Glacier. Mount Hope and the Gateway before them. | 346 | |

| From photographs by C. S. Wright. | ||

| Plate IV. | Transit sketch for the Lower Glacier Depôt. December 11, 1911. Showing the Pillar Rock, mainland mountains, the Gateway or Gap, and the beginning of the main Beardmore Glacier outlet on to the Barrier. | 352 |

| From sketches by Dr. Edward A. Wilson. | ||

| Plate V. | Mount F. L. Smith and the land to the North-West. December 12, 1911. | 354 |

| From sketches by Dr. Edward A. Wilson. | ||

| Plate VI. | Mount Elizabeth, Mount Anne and Socks Glacier. December 13, 1911. | 356 |

| From sketches by Dr. Edward A. Wilson. | ||

| Mount Patrick. December 16, 1911. | 358 | |

| From a sketch by Dr. Edward A. Wilson. | ||

| Plate VII. | From Mount Deakin to Mount Kinsey, showing the outlet of the Keltie Glacier, and Mount Usher in the distance. December 19, 1911. | 362 |

| From sketches by Dr. Edward A. Wilson. | ||

| Our night Camp at the foot of the Buckley Island ice-falls. December 20, 1911. Buckley Island in the background. Note ablation pits in the snow. | 364 | |

| From a photograph by C. S. Wright. | ||

| The Adams Mountains. | 382 | |

| The First Return Party on the Beardmore Glacier. | 382 | |

| From photographs by C. S. Wright. | ||

| Camp below the Cloudmaker. Note pressure ridges in the middle distance. | 390 | |

| From a photograph by C. S. Wright. | ||

| Plate VIII. | From Mount Kyffin to Mount Patrick. December 14, 1911. | 392 |

| From sketches by Dr. Edward A. Wilson. | ||

| View from Arrival Heights northwards to Cape Evans and the Dellbridge Islands. | 428 | |

| Cape Royds from Cape Barne, with the frozen McMurdo Sound. | 428 | |

| From photographs by F. Debenham. | ||

| Cape Evans in Winter. This view is drawn when looking northwards from under the Ramp. | 440 | |

| From a water-colour drawing by Dr. Edward A. Wilson. | ||

| North Bay and the snout of the Barne Glacier from Cape Evans. | 448 | |

| From a photograph by F. Debenham. | ||

| The Mule Party leaves Cape Evans. October 29, 1912. | 472 | |

| From a photograph by F. Debenham. | ||

| The Dog Party leaves Hut Point. November 1, 1912. | 478 | |

| From a photograph by F. Debenham. | ||

| "Atch": E. L. Atkinson, commanding the Main Landing Party after the death of Scott. | 492 | |

| "Titus" Oates. | 492 | |

| From photographs by C. S. Wright. | ||

| The Tent left by Amundsen at the South Pole (Polheim). | 506 | |

| From a sketch by Dr. Edward A. Wilson. | ||

| Buckley Island, where the fossils were found. | 518 | |

| From a photograph by C. S. Wright. | ||

| Plate IX. | Buckley Island, sketched during the evening of December 21, 1911. | 522 |

| From sketches by Dr. Edward A. Wilson. | ||

| Mount Kyffin, sketched on December 13, 1911. | 524 | |

| From a sketch by Dr. Edward A. Wilson. | ||

| Where Evans died, showing the Pillar Rock near which the Lower Glacier Depôt was made. Sketched on December 11, 1911. | 526 | |

| From a sketch by Dr. Edward A. Wilson. | ||

| Sledging in a high wind: the floor-cloth of the tent is the sail. | 530 | |

| From a sketch by Dr. Edward A. Wilson. | ||

| Plate X. | Mount Longstaff, sketched on December 1, 1911. See also Plate III., p. 338 | 532 |

| From sketches by Dr. Edward A. Wilson. | ||

| A Blizzard Camp: the half-buried sledge is in the foreground. | 536 | |

| From a sketch by Dr. Edward A. Wilson. | ||

| The Polar Journey. | 542 |

Inside was pandemonium. Most men had gone to bed, and I have a blurred memory of men in pyjamas and dressing-gowns getting hold of me and trying to get the chunks of armour which were my clothes to leave my body. Finally they cut them off and threw them into an angular heap at the foot of my bunk. Next morning they were a sodden mass weighing 24 lbs. Bread and jam, and cocoa; showers of questions; "You know this is the hardest journey ever made," from Scott; a broken record of George Robey on the gramophone which started us laughing until in our weak state we found it difficult to stop. I have no doubt that I had not stood the journey as well as Wilson: my jaw had dropped when I came in, so they tell me. Then into my warm blanket bag, and I managed to keep awake just long enough to think that Paradise must feel something like this.

We slept ten thousand thousand years, were wakened to find everybody at breakfast, and passed a wonderful day, lazying about, half asleep and wholly happy, listening to the news and answering questions. "We are looked upon as beings who have come from another world. This afternoon I had a shave after soaking my face in a hot sponge, and then a bath. Lashly had already cut my hair. Bill looks very thin and we are all very blear-eyed from want of sleep. I have not much appetite, my mouth is very dry and throat sore with a troublesome hacking cough which I have had all the journey. My taste is gone. We are getting badly spoiled, but our beds are the height of all our pleasures."[168]

But this did not last long:

"Another very happy day doing nothing. After falling asleep two or three times I went to bed, read Kim, and slept. About two hours after each meal we all want another, and after a tremendous supper last night we had another meal before turning in. I have my taste back but all our fingers are impossible, they might be so many pieces of lead except for the pins and needles feeling in them which we have also got in our feet. My toes are very bulbous and some toe-nails are coming off. My left heel is one big burst blister. Going straight out of a warm bed into a strong wind outside nearly bowled me over. I felt quite faint, and pulled myself together thinking it was all nerves: but it began to come on again and I had to make for the hut as quickly as possible. Birdie is now full of schemes for doing the trip again next year. Bill says it is too great a risk in the darkness, and he will not consider it, though he thinks that to go in August might be possible."[169]

And again a day or two later:

"I came in covered with a red rash which is rather ticklish. My ankles and knees are a bit puffy, but my feet are not so painful as Bill's and Birdie's. Hands itch a bit. We must be very weak and worn out, though I think Birdie is the strongest of us. He seems to be picking up very quickly. Bill is still very worn and rather haggard. The kindness of everybody would spoil an angel."[170]

I have put these personal experiences down from my diary because they are the only contemporary record I possess. Scott's own diary at this time contains the statement: "The Crozier party returned last night after enduring for five weeks the hardest conditions on record. They looked more weather-worn than any one I have yet seen. Their faces were scarred and wrinkled, their eyes dull, their hands whitened and creased with the constant exposure to damp and cold, yet the scars of frost-bite were very few ... to-day after a night's rest our travellers are very different in appearance and mental capacity."[171]

"Atch has been lost in a blizzard," was the news which we got as soon as we could grasp anything. Since then he has spent a year of war in the North Sea, seen the Dardanelles campaign, and much fighting in France, and has been blown up in a monitor. I doubt whether he does not reckon that night the worst of the lot. He ought to have been blown into hundreds of little bits, but always like some hardy indiarubber ball he turns up again, a little dented, but with the same tough elasticity which refuses to be hurt. And with the same quiet voice he volunteers for the next, and tells you how splendid everybody was except himself.

It was the blizzard of July 4, when we were lying in the windless bight on our way to Cape Crozier, and we knew it must be blowing all round us. At any rate it was blowing at Cape Evans, though it eased up in the afternoon, and Atkinson and Taylor went up the Ramp to read the thermometers there. They returned without great difficulty, and some discussion seems to have arisen as to whether it was possible to read the two screens on the sea-ice. Atkinson said he would go and read that in North Bay: Gran said he was going to South Bay. They started independently at 5.30 p.m. Gran returned an hour and a quarter afterwards. He had gone about two hundred yards.

Atkinson had not gone much farther when he decided that he had better give it up, so he turned and faced the wind, steering by keeping it on his cheek. We discovered afterwards that the wind does not blow quite in the same direction at the end of the Cape as it does just where the hut lies. Perhaps it was this, perhaps his left leg carried him a little farther than his right, perhaps it was that the numbing effect of a blizzard on a man's brain was already having its effect, certainly Atkinson does not know himself, but instead of striking the Cape which ran across his true front, he found himself by an old fish trap which he knew was 200 yards out on the sea-ice. He made a great effort to steady himself and make for the Cape, but any one who has stood in a blizzard will understand how difficult that is. The snow was a blanket raging all round him, and it was quite dark. He walked on, and found nothing.

Everything else is vague. Hour after hour he staggered about: he got his hand badly frost-bitten: he found pressure: he fell over it: he was crawling in it, on his hands and knees. Stumbling, tumbling, tripping, buffeted by the endless lash of the wind, sprawling through miles of punishing snow, he still seems to have kept his brain working. He found an island, thought it was Inaccessible, spent ages in coasting along it, lost it, found more pressure, and crawled along it. He found another island, and the same horrible, almost senseless, search went on. Under the lee of some rocks he waited for a time. His clothing was thin though he had his wind-clothes, and, a horrible thought if this was to go on, he had boots on his feet instead of warm finnesko. Here also he kicked out a hole in a drift where he might have more chance if he were forced to lie down. For sleep is the end of men who get lost in blizzards. Though he did not know it he must now have been out more than four hours.

There was little chance for him if the blizzard continued, but hope revived when the moon showed in a partial lull. It is wonderful that he was sufficiently active to grasp the significance of this, and groping back in his brain he found he could remember the bearing of the moon from Cape Evans when he went to bed the night before. The hut must be somewhere over there: this must be Inaccessible Island! He left the island and made in that direction, but the blizzard came down again with added force and the moon was blotted out. He tried to return to the island and failed: then he stumbled on another island, perhaps the same one, and waited. Again the lull came, and again he set off, and walked and walked, until he recognized Inaccessible Island on his left. Clearly he must have been under Great Razorback Island and this is some four miles from Cape Evans. The moon still showed, and on he walked and then at last he saw a flame.

Atkinson's continued absence was not noticed at the hut until dinner was nearly over at 7.15; that is, until he had been absent about two hours. The wind at Cape Evans had dropped though it was thick all round, and no great anxiety was felt: some went out and shouted, others went north with a lantern, and Day arranged to light a paraffin flare on Wind Vane Hill. Atkinson never experienced this lull, and having seen the way blizzards will sweep down the Strait though the coastline is comparatively clear and calm, I can understand how he was in the thick of it all the time. I feel convinced that most of these blizzards are local affairs. The party which had gone north returned at 9.30 without news, and Scott became seriously alarmed. Between 9.30 and 10 six search parties started out. But time was passing and Atkinson had been away more than six hours.

The light which Atkinson had seen was a flare of tow soaked in petrol lit by Day at Cape Evans. He corrected his course and before long was under the rock upon which Day could be seen working like some lanky devil in one of Dante's hells. Atkinson shouted again and again but could not attract his attention, and finally walked almost into the hut before he was found by two men searching the Cape. "It was all my own damned fault," he said, "but Scott never slanged me at all." I really think we should all have been as merciful! Wouldn't you?

And that was that: but he had a beastly hand.

Theoretically the sun returned to us on August 23. Practically there was nothing to be seen except blinding drift. But we saw his upper limb two days later. In Scott's words the daylight came "rushing" at us. Two spring journeys were contemplated; and with preparations for the Polar Journey, and the ordinary routine work of the station, everybody had as much on his hands as he could get through.

Lieutenant Evans, Gran and Forde volunteered to go out to Corner Camp and dig out this depôt as well as that of Safety Camp. They started on September 9 and camped on the sea-ice beyond Cape Armitage that night, the minimum temperature being -45°. They dug out Safety Camp next morning, and marched on towards Corner Camp. The minimum that night was -62.3°. The next evening they made their night camp as a blizzard was coming up, the temperature at the same time being -34.5° and minimum for the night -40°. This is an extremely low temperature for a blizzard. They made a start in a very cold wind the next afternoon (September 12) and camped at 8.30 p.m. That night was bitterly cold and they found that the minimum showed -73.3° for that night. Evans reports adversely on the use of the eider-down bag and inner tent, but here none of our Winter Journey men would agree with him.[172] Most of September 13th was spent in digging out Corner Camp which they left at 5 p.m., intending to travel back to Hut Point without stopping except for meals. They marched all through that night with two halts for meals and arrived at Hut Point at 3 p.m. on September 14, having covered a distance of 34.6 statute miles. They reached Cape Evans the following day after an absence of 6½ days.[173]

During this journey Forde got his hand badly frost-bitten which necessitated his return in the Terra Nova in March 1912. He owed a good deal to the skilful treatment Atkinson gave it.

Wilson was still looking grey and drawn some days, and I was not too fit, but Bowers was indefatigable. Soon after we got in from Cape Crozier he heard that Scott was going over to the Western Mountains: somehow or other he persuaded Scott to take him, and they started with Seaman Evans and Simpson on September 15 on what Scott calls "a remarkably pleasant and instructive little spring journey,"[174] and what Bowers called a jolly picnic.

This picnic started from the hut in a -40° temperature, dragging 180 lbs. per man, mainly composed of stores for the geological party of the summer. They penetrated as far north as Dunlop Island and turned back from there on September 24, reaching Cape Evans on September 29, marching twenty-one miles (statute) into a blizzard wind with occasional storms of drift and a temperature of -16°: and they marched a little too long; for a storm of drift came against them and they had to camp. It is never very easy pitching a tent on sea-ice because there is not very much snow on the ice: on this occasion it was only after they had detached the inner tent, which was fastened to the bamboos, that they could hold the bamboos, and then it was only inch by inch that they got the outer cover on. At 9 p.m. the drift took off though the wind was as strong as ever, and they decided to make for Cape Evans. They arrived at 1.15 a.m. after one of the most strenuous days which Scott could remember: and that meant a good deal. Simpson's face was a sight! During his absence Griffith Taylor became meteorologist-in-chief. He was a greedy scientist, and he also wielded a fluent pen. Consequently his output during the year and a half which he spent with us was large, and ranged from the results of the two excellent scientific journeys which he led in the Western Mountains, to this work during the latter half of September. He was a most valued contributor to The South Polar Times, and his prose and poetry both had a bite which was never equalled by any other of our amateur journalists. When his pen was still, his tongue wagged, and the arguments he led were legion. The hut was a merrier place for his presence. When the weather was good he might be seen striding over the rocks with a complete disregard of the effect on his clothes: he wore through a pair of boots quicker than anybody I have ever known, and his socks had to be mended with string. Ice movement and erosion were also of interest to him, and almost every day he spent some time in studying the slopes and huge ice-cliffs of the Barne Glacier, and other points of interest. With equal ferocity he would throw himself into his curtained bunk because he was bored, or emerge from it to take part in some argument which was troubling the table. His diary must have been almost as long as the reports he wrote for Scott of his geological explorations. He was a demon note-taker, and he had a passion for being equipped so that he could cope with any observation which might turn up. Thus Old Griff on a sledge journey might have notebooks protruding from every pocket, and hung about his person, a sundial, a prismatic compass, a sheath knife, a pair of binoculars, a geological hammer, chronometer, pedometer, camera, aneroid and other items of surveying gear, as well as his goggles and mitts. And in his hand might be an ice-axe which he used as he went along to the possible advancement of science, but the certain disorganization of his companions.

His gaunt, untamed appearance was atoned for by a halo of good-fellowship which hovered about his head. I am sure he must have been an untidy person to have in your tent: I feel equally sure that his tent-mates would have been sorry to lose him. His gear took up more room than was strictly his share, and his mind also filled up a considerable amount of space. He always bulked large, and when he returned to the Australian Government, which had lent him for the first two sledging seasons, he left a noticeable gap in our company.

From the time we returned from Cape Crozier until now Scott had been full of buck. Our return had taken a weight off his mind: the return of the daylight was stimulating to everybody: and to a man of his impatient and impetuous temperament the end of the long period of waiting was a relief. Also everything was going well. On September 10 he writes with a sigh of relief that the detailed plans for the Southern Journey are finished at last. "Every figure has been checked by Bowers, who has been an enormous help to me. If the motors are successful, we shall have no difficulty in getting to the Glacier, and if they fail, we shall still get there with any ordinary degree of good fortune. To work three units of four men from that point onwards requires no small provision, but with the proper provision it should take a good deal to stop the attainment of our object. I have tried to take every reasonable possibility of misfortune into consideration, and to so organize the parties as to be prepared to meet them. I fear to be too sanguine, yet taking everything into consideration I feel that our chances ought to be good."[175]

And again he writes: "Of hopeful signs for the future none are more remarkable than the health and spirit of our people. It would be impossible to imagine a more vigorous community, and there does not seem to be a single weak spot in the twelve good men and true who are chosen for the Southern advance. All are now experienced sledge travellers, knit together with a bond of friendship that has never been equalled under such circumstances. Thanks to these people, and more especially to Bowers and Petty Officer Evans, there is not a single detail of our equipment which is not arranged with the utmost care and in accordance with the tests of experience."[176]

Indeed Bowers had been of the very greatest use to Scott in the working out of these plans. Not only had he all the details of stores at his finger-tips, but he had studied polar clothing and polar food, was full of plans and alternative plans, and, best of all, refused to be beaten by any problem which presented itself. The actual distribution of weights between dogs, motors and ponies, and between the different ponies, was largely left in his hands. We had only to lead our ponies out on the day of the start and we were sure to find our sledges ready, each with the right load and weight. To the leader of an expedition such a man was worth his weight in gold.

But now Scott became worried and unhappy. We were running things on a fine margin of transport, and during the month before we were due to start mishap followed mishap in the most disgusting way. Three men were more or less incapacitated: Forde with his frozen hand, Clissold who concussed himself by a fall from a berg, and Debenham who hurt his knee seriously when playing foot-ball. One of the ponies, Jehu, was such a crock that at one time it was decided not to take him out at all: and very bad opinions were also held of Chinaman. Another dog died of a mysterious disease. "It is trying," writes Scott, "but I am past despondency. Things must take their course."[177] And "if this waiting were to continue it looks as though we should become a regular party of 'crocks.'"[178]

Then on the top of all this came a bad accident to one of the motor axles on the eve of departure. "To-night the motors were to be taken on to the floe. The drifts made the road very uneven, and the first and best motor overrode its chain; the chain was replaced and the machine proceeded, but just short of the floe was thrust to a steep inclination by a ridge, and the chain again overrode the sprockets; this time by ill fortune Day slipped at the critical moment and without intention jammed the throttle full on. The engine brought up, but there was an ominous trickle of oil under the back axle, and investigation showed that the axle casing (aluminium) had split. The casing had been stripped and brought into the hut: we may be able to do something to it, but time presses. It all goes to show that we want more experience and workshops. I am secretly convinced that we shall not get much help from the motors, yet nothing has ever happened to them that was unavoidable. A little more care and foresight would make them splendid allies. The trouble is that if they fail, no one will ever believe this."[179]

In the meantime Meares and Dimitri ran out to Corner Camp from Hut Point twice with the two dog-teams. The first time they journeyed out and back in two days and a night, returning on October 15; and another very similar run was made before the end of the month.

The motor party was to start first, but was delayed until October 24. They were to wait for us in latitude 80° 30´, man-hauling certain loads on if the motors broke down. The two engineers were Day and Lashly, and their two helpers, who steered by pulling on a rope in front, were Lieutenant Evans and Hooper. Scott was "immensely eager that these tractors should succeed, even though they may not be of great help to our Southern advance. A small measure of success will be enough to show their possibilities, their ability to revolutionize polar transport."[180]

Lashly, as the reader may know by now, was a chief stoker in the Navy, and accompanied Scott on his Plateau Journey in the Discovery days. The following account of the motors' chequered career is from his diary, and for permission to include here both it and the story of the adventures of the Second Return Party, an extraordinarily vivid and simple narrative, I cannot be too grateful.

After the motors had been two days on the sea-ice on their way to Hut Point Lashly writes on 26th October 1911:

"Kicked off at 9.30; engine going well, surface much better, dropped one can of petrol each and lubricating oil, lunched about two miles from Hut Point. Captain Scott and supporting party came from Cape Evans to help us over blue ice, but they were not required. Got away again after lunch but was delayed by the other sledge not being able to get along, it is beginning to dawn on me the sledges are not powerful enough for the work as it is one continual drag over this sea-ice, perhaps it will improve on the barrier, it seems we are going to be troubled with engine overheating; after we have run about three-quarters to a mile it is necessary to stop at least half an hour to cool the engine down, then we have to close up for a few minutes to allow the carbrutta to warm up or we can't get the petrol to vaporize; we are getting new experiences every day. We arrived at Hut Point and proceeded to Cape Armitage it having come on to snow pretty thickly, so we pitched our tent and waited for the other car to come up, she has been delayed all the afternoon and not made much headway. At 6.30 Mr. Bowers and Mr. Garrard came out to us and told us to come back to Hut Point for the night, where we all enjoyed ourselves with a good hoosh and a nice night with all hands.

"27th October 1911.

"This morning being fine made our way out to the cars and got them going after a bit of trouble, the temperature being a bit low. I got away in good style, the surface seems to be improving, it is better for running on but very rough and the overheating is not overcome nor likely to be as far as I can see. Just before arriving at the Barrier my car began to develop some strange knocking in the engine, but with the help of the party with us I managed to get on the Barrier, the other car got up the slope in fine style and waited for me to come up; as my engine is giving trouble we decided to camp, have lunch and see what is the matter. On opening the crank chamber we found the crank brasses broke into little pieces, so there is nothing left to do but replace them with the spare ones; of course this meant a cold job for Mr. Day and myself, as handling metal on the Barrier is not a thing one looks forward to with pleasure. Anyhow we set about it after Lieutenant Evans and Hooper had rigged up a screen to shelter us a bit, and by 10 p.m. we were finished and ready to proceed, but owing to a very low temperature we found it difficult to get the engines to go, so we decided to camp for the night.

"28th October 1911.

"Turned out and had another go at starting which took some little time owing again to the low temperature. We got away but again the trouble is always staring us in the face, overheating, and the surface is so bad and the pull so heavy and constant that it looks we are in for a rough time. We are continually waiting for one another to come up, and every time we stop something has to be done, my fan got jammed and delayed us some time, but have got it right again. Mr. Evans had to go back for his spare gear owing to some one [not] bringing it out in mistake; he had a good tramp as we were about 15 miles out from Hut Point.

"29th October 1911.

"Again we got away, but did not get far before the other car began to give trouble. I went back to see what was the matter, it seems the petrol is dirty due perhaps to putting in a new drum, anyhow got her up and camped for lunch. After lunch made a move, and all seemed to be going well when Mr. Day's car gave out at the crank brasses the same as mine, so we shall have to see what is the next best thing to do.

"30th October 1911.

"This morning before getting the car on the way had to reconstruct our loads as Mr. Day's car is finished and no more use for further service. We have got all four of us with one car now, things seems to be going fairly well, but we are still troubled with the overheating which means to say half our time is wasted. We can see dawning on us the harness before long. We covered seven miles and camped for the night. We are now about six miles from Corner Camp.

"31st October 1911.

"Got away with difficulty, and nearly reached Corner Camp, but the weather was unkind and forced us to camp early. One thing we have been able to bring along a good supply of pony food and most of the man food, but so far the motor sledges have proved a failure.

"1st November 1911.

"Started away with the usual amount of agony, and soon arrived at Corner Camp where we left a note to Captain Scott explaining the cause of our breakdown. I told Mr. Evans to say this sledge won't go much farther. After getting about a mile past Corner Camp my engine gave out finally, so here is an end to the motor sledges. I can't say I am sorry because I am not, and the others are, I think, of the same opinion as myself. We have had a heavy task pulling the heavy sledges up every time we stopped, which was pretty frequent, even now we have to start man-hauling we shall not be much more tired than we have already been at night when we had finished. Now comes the man-hauling part of the show, after reorganizing our sledge and taking aboard all the man food we can pull, we started with 190 lbs. per man, a strong head wind made it a bit uncomfortable for getting along, anyhow we made good about three miles and camped for the night. The surface not being very good made the travelling a bit heavy.

"After three days' man-hauling.

"5th November 1911.

"Made good about 14½ miles, if the surface would only remain as it is now we could get along pretty well. We are now thinking of the ponies being on their way, hope they will get better luck than we had with the motor sledges, but by what I can see they will have a tough time of it.

"6th November 1911.

"To-day we have worked hard and covered a good distance 12 miles, surface rough but slippery, all seems to be going pretty well, but we have generally had enough by the time comes for us to camp.

"7th November 1911.

"We have again made good progress, but the light was very trying, sometimes we could not see at all where we were going. I tried to find some of the Cairns that were built by the Depôt Party last year, came upon one this afternoon which is about 20 miles from One Ton Depôt, so at the rate we have been travelling we ought to reach there some time to-morrow night. Temperature to-day was pretty low, but we are beginning to get hardened into it now.

"8th November 1911.

"Made a good start, but the surface is getting softer every day and makes our legs ache; we arrived at One Ton Depôt and camped. Then proceeded to dig out some of the provisions, we have to take on all the man food we can, this is a wild-looking place no doubt, have not seen anything of the ponies.

"9th November 1911.

"To-day we have started on the second stage of our journey. Our orders are to proceed one degree south of One Ton Depôt and wait for the ponies and dogs to come up with us; as we have been making good distances each day, the party will hardly overtake us, but we have found to-day the load is much heavier to drag. We have just over 200 lbs. per man, and we have been brought up on several occasions, and to start again required a pretty good strain on the rope, anyhow we done 10½ miles, a pretty good show considering all things.

"10th November 1911.

"Again we started off with plenty of vim, but it was jolly tough work, and it begins to tell on all of us; the surface to-day is covered with soft crystals which don't improve things. To-night Hooper is pretty well done up, but he have stuck it well and I hope he will, although he could not tackle the food in the best of spirits, we know he wanted it. Mr. Evans, Mr. Day and myself could eat more, as we are just beginning to feel the tightening of the belt. Made good 11¼ miles and we are now building cairns all the way, one about three miles: then again at lunch and one in the afternoon and one at night. This will keep us employed.

"11th November 1911.

"To-day it has been very heavy work. The surface is very bad and we are pretty well full up, but not with food; man-hauling is no doubt the hardest work one can do, no wonder the motor sledges could not stand it. I have been thinking of the trials I witnessed of the motor engines in Wolseley's works in Birmingham, they were pretty stiff but nothing compared to the drag of a heavy load on the Barrier surface.

"12th November 1911.

"To-day have been similar to the two previous days, but the light have been bad and snow have been falling which do not improve the surface; we have been doing 10 miles a day Geographical and quite enough too as we have all had enough by time it goes Camp.

"13th November 1911.

"The weather seems to be on the change. Should not be surprised if we don't get a blizzard before long, but of course we don't want that. Hooper seems a bit fagged but he sticks it pretty well. Mr. Day keeps on plodding, his only complaint is should like a little more to eat.

"14th November 1911.

"When we started this morning Mr. Evans said we had about 15 miles to go to reach the required distance. The hauling have been about the same, but the weather is somewhat finer and the blizzard gone off. We did 10 miles and camped; have not seen anything of the main party yet but shall not be surprised to see them at any time.

"15th November 1911.

"We are camped after doing five miles where we are supposed to be [lat. 80° 32´]; now we have to wait the others coming up. Mr. Evans is quite proud to think we have arrived before the others caught us, but we don't expect they will be long although we have nothing to be ashamed of as our daily distance have been good. We have built a large cairn this afternoon before turning in. The weather is cold but excellent."

They waited there six days before the pony party arrived, when the Upper Barrier Depôt (Mount Hooper) was left in the cairn.

[168] My own diary.

[169] Ibid.

[170] Ibid.

[171] Scott's Last Expedition, vol. i. p. 361.

[172] Scott's Last Expedition, vol. ii. p. 293.

[173] Ibid. pp. 291-297; written by Lieutenant Evans.

[174] Ibid. vol. i. p. 409.

[175] Scott's Last Expedition, vol. i. p. 403.

[176] Ibid. p. 404.

[177] Scott's Last Expedition, vol. i. p. 425.

[178] Ibid. p. 437.

[179] Ibid. p. 429.

[180] Ibid. p. 438.

Tennyson, Ulysses.

Take it all in all it is wonderful that the South Pole was reached so soon after the North Pole had been conquered. From Cape Columbia to the North Pole, straight going, is 413 geographical miles, and Peary who took on his expedition 246 dogs, covered this distance in 37 days. From Hut Point to the South Pole and back is 1532 geographical or 1766 statute miles, the distance to the top of the Beardmore Glacier alone being more than 100 miles farther than Peary had to cover to the North Pole. Scott travelled from Hut Point to the South Pole in 75 days, and to the Pole and back to his last camp in 147 days, a period of five months. A. C.-G.

(All miles are geographical unless otherwise stated.)

The departure from Cape Evans at 11 p.m. on November 1 is described by Griffith Taylor, who started a few days later on the second Geological Journey with his own party:

"On the 31st October the pony parties started. Two weak ponies led by Atkinson and Keohane were sent off first at 4.30, and I accompanied them for about a mile. Keohane's pony rejoiced in the name of Jimmy Pigg, and he stepped out much better than his fleeter-named mate Jehu. We heard through the telephone of their safe arrival at Hut Point.

"Next morning the Southern Party finished their mail, posting it in the packing case on Atkinson's bunk, and then at 11 a.m. the last party were ready for the Pole. They had packed the sledges overnight, and they took 20 lbs. personal baggage. The Owner had asked me what book he should take. He wanted something fairly filling. I recommended Tyndall's Glaciers—if he wouldn't find it 'coolish.' He didn't fancy this! So then I said, 'Why not take Browning, as I'm doing?' And I believe that he did so.

"Wright's pony was the first harnessed to its sledge. Chinaman is Jehu's rival for last place, and as some compensation is easy to harness. Seaman Evans led Snatcher, who used to rush ahead and take the lead as soon as he was harnessed. Cherry had Michael, a steady goer, and Wilson led Nobby—the pony rescued from the killer whales in March. Scott led out Snippets to the sledges, and harnessed him to the foremost, with little Anton's help—only it turned out to be Bowers' sledge! However he transferred in a few minutes and marched off rapidly to the south. Christopher, as usual, behaved like a demon. First they had to trice his front leg up tight under his shoulder, then it took five minutes to throw him. The sledge was brought up and he was harnessed in while his head was held down on the floe. Finally he rose up, still on three legs, and started off galloping as well as he was able. After several violent kicks his foreleg was released, and after more watch-spring flicks with his hind legs he set off fairly steadily. Titus can't stop him when once he has started, and will have to do the fifteen miles in one lap probably!

"Dear old Titus—that was my last memory of him. Imperturbable as ever; never hasty, never angry, but soothing that vicious animal, and determined to get the best out of most unpromising material in his endeavour to do his simple duty.

"Bowers was last to leave. His pony, Victor, nervous but not vicious, was soon in the traces. I ran to the end of the Cape and watched the little cavalcade—already strung out into remote units—rapidly fade into the lonely white waste to southward.

"That evening I had a chat with Wilson over the telephone from the Discovery Hut—my last communication with those five gallant spirits."[181]

All the ponies arrived at Hut Point by 4 p.m., just in time to escape a stiff blow. Three of them were housed with ourselves inside the hut, the rest being put into the verandah. The march showed that with their loads the speed of the different ponies varied to such an extent that individuals were soon separated by miles. "It reminded me of a regatta or a somewhat disorganized fleet with ships of very unequal speed."[182]

It was decided to change to night marching, and the following evening we proceeded in the following order, which was the way of our going for the present. The three slowest ponies started first, namely, Jehu with Atkinson, Chinaman with Wright, James Pigg with Keohane. This party was known as the Baltic Fleet.

Two hours later Scott's party followed; Scott with Snippets, Wilson with Nobby, and myself with Michael.

Both these parties camped for lunch in the middle of the night's march. After another hour the remaining four men set to work to get Christopher into his sledge; when he was started they harnessed in their own ponies as quickly as possible and followed, making a non-stop run right through the night's march. It was bad for men and ponies, but it was impossible to camp in the middle of the march owing to Christopher. The composition of this party was, Oates with Christopher, Bowers with Victor, Seaman Evans with Snatcher, Crean with Bones.

Each of these three parties was self-contained with tent, cooker and weekly bag, and the times of starting were so planned that the three parties arrived at the end of the march about the same time.

There was a strong head wind and low drift as we rounded Cape Armitage on our way to the Barrier and the future. Probably there were few of us who did not wonder when we should see the old familiar place again.

Scott's party camped at Safety Camp as the Baltic fleet were getting under weigh again. Soon afterwards Ponting appeared with a dog sledge and a cinematograph,—how anomalous it seemed—which "was up in time to catch the flying rearguard which came along in fine form, Snatcher leading and being stopped every now and again—a wonderful little beast. Christopher had given the usual trouble when harnessed, but was evidently subdued by the Barrier Surface. However, it was not thought advisable to halt him, and so the party fled through in the wake of the advance guard."[183]

Immediately afterwards Scott's party packed up. "Good-bye and good luck," from Ponting, a wave of the hand not holding in a frisky pony and we had left the last link with the hut. "The future is in the lap of the gods; I can think of nothing left undone to deserve success."[184]

The general scheme was to average 10 miles (11.5 statute) a day from Hut Point to One Ton Depôt with the ponies lightly laden. From One Ton to the Gateway a daily average of 13 miles (15 statute) was necessary to carry twenty-four weekly units of food for four men each to the bottom of the glacier. This was the Barrier Stage of the journey, a distance of 369 miles (425 statute) as actually run on our sledge-meter. The twenty-four weekly units of food were to carry the Polar Party and two supporting parties forward to their farthest point, and back again to the bottom of the Beardmore, where three more units were to be left in a depôt.[185]

All went well this first day on the Barrier, and encouraging messages left on empty petrol drums told us that the motors were going well when they passed. But the next day we passed five petrol drums which had been dumped. This meant that there was trouble, and some 14 miles from Hut Point we learned that the big end of the No. 2 cylinder of Day's motor had broken, and half a mile beyond we found the motor itself, drifted up with snow, and looking a mournful wreck. The next day's march (Sunday, November 5, a.m.) brought us to Corner Camp. There were a few legs down crevasses during the day but nothing to worry about.

From here we could see to the South an ominous mark in the snow which we hoped might not prove to be the second motor. It was: "the big end of No. 1 cylinder had cracked, the machine otherwise in good order. Evidently the engines are not fitted to working in this climate, a fact that should be certainly capable of correction. One thing is proved; the system of propulsion is altogether satisfactory."[186] And again: "It is a disappointment. I had hoped better of the machines once they got away on the Barrier Surface."[187]

Scott had set his heart upon the success of the motors. He had run them in Norway and Switzerland; and everything was done that care and forethought could suggest. At the back of his mind, I feel sure, was the wish to abolish the cruelty which the use of ponies and dogs necessarily entails. "A small measure of success will be enough to show their possibilities, their ability to revolutionize polar transport. Seeing the machines at work to-day [leaving Cape Evans] and remembering that every defect so far shown is purely mechanical, it is impossible not to be convinced of their value. But the trifling mechanical defects and lack of experience show the risk of cutting out trials. A season of experiment with a small workshop at hand may be all that stands between success and failure."[188] I do not believe that Scott built high hopes on these motors: but it was a chance to help those who followed him. Scott was always trying to do that.

Did they succeed or fail? They certainly did not help us much, the motor which travelled farthest drawing a heavy load to just beyond Corner Camp. But even so fifty statute miles is fifty miles, and that they did it at all was an enormous advance. The distance travelled included hard and soft surfaces, and we found later when the snow bridges fell in during the summer that this car had crossed safely some broad crevasses. Also they worked in temperatures down to -30° Fahr. All this was to the good, for no motor-driven machine had travelled on the Barrier before. The general design seemed to be right, all that was now wanted was experience. As an experiment they were successful in the South, but Scott never knew their true possibilities; for they were the direct ancestors of the 'tanks' in France.

Night-marching had its advantages and disadvantages. The ponies were pulling in the colder part of the day and resting in the warm, which was good. Their coats dried well in the sun, and after a few days to get accustomed to the new conditions, they slept and fed in comparative comfort. On the other hand the pulling surface was undoubtedly better when the sun was high and the temperature warmer. Taking one thing with another there was no doubt that night-marching was better for ponies, but we seldom if ever tried it man-hauling.

Camp On The Barrier—E. A. Wilson, del.

Just now there was an amazing difference between day and night conditions. At midnight one was making short work of everything, nursing fingers after doing up harness with minus temperatures and nasty cold winds: by supper time the next morning we were sitting on our sledges writing up our diaries or meteorological logs, and even dabbling our bare toes in the snow, but not for long! Shades of darkness! How different all this was from what we had been through. My personal impression of this early summer sledging on the Barrier was one of constant wonder at its comfort. One had forgotten that a tent could be warm and a sleeping-bag dry: so deep were the contrary impressions that only actual experience was convincing. "It is a sweltering day, the air breathless, the glare intense—one loses sight of the fact that the temperature is low [-22°], one's mind seeks comparison in hot sunlit streets and scorching pavements, yet six hours ago my thumb was frost-bitten. All the inconveniences of frozen footwear and damp clothes and sleeping-bags have vanished entirely."[189]

We could not expect to get through this windy area of Corner Camp without some bad weather. The wind-blown surface improved, the ponies took their heavier loads with ease, but as we came to our next camp it was banking up to the S.E. and the breeze freshened almost immediately. We built pony walls hurriedly and by the time we had finished supper it was blowing force 5 (a.m. November 6, Camp 4). There was a moderate gale with some drift all day which increased to force 8 with more drift at night. It was impossible to march. The drift took off a bit the next morning, and Meares and Dimitri with the two dog-teams appeared and camped astern of us. This was according to previous plan by which the dog-teams were to start after us and catch us up, since they travelled faster than the ponies. "The snow and drift necessitated digging out ponies again and again to keep them well sheltered from the wind. The walls made a splendid lee, but some sledges at the extremities were buried altogether, and our tent being rather close to windward of our wall got the back eddy and was continually being snowed up above the door. After noon the snow ceased except for surface drift. Snatcher knocked his section of the wall over, and Jehu did so more than ever. All ponies looked pretty miserable, as in spite of the shelter they were bunged up, eyes and all, in drift which had become ice and could not be removed without considerable difficulty."[190]

Towards evening it ceased drifting altogether, but a wind, force 4, kept up with disconcerting regularity. Eventually Atkinson's party got away at midnight. "Castle Rock is still visible, but will be closed by the north end of White Island in the next march—then good-bye to the old landmarks for many a long day."[191]

The next day (November 8-9) "started at midnight and had a very pleasant march. Truly sledging in such weather is great. Mounts Discovery and Morning, which we gradually closed, looked fine in the general panorama of mountains. We are now nearly abreast the north end of the Bluff. We all came up to camp together this morning: it looked like a meet of the hounds, and Jehu ran away!!!"[192]

The next march was just the opposite. Wind force 5 to 6 and falling snow. "The surface was very slippery in parts and on the hard sastrugi it was a case of falling or stumbling continually. The light got so bad that one might have been walking in the clouds for all that could be discerned, and yet it was only snowing slightly. The Bluff became completely obscured, and the usual signs of a blizzard were accentuated.

"At lunch camp Scott packed up and followed us. We overhauled Atkinson about 1½ hours later, he having camped, and we were not sorry, as in addition to marching against a fresh southerly breeze the light brought a tremendous strain on the eyes in following tracks."[193] A little more than eight miles for the day's total.

We carried these depressing conditions for three more marches, that is till the morning of November 13. The surface was wretched, the weather horrid, the snow persistent, covering everything with soft downy flakes, inch upon inch, and mile upon mile. There are glimpses of despondency in the diaries. "If this should come as an exception, our luck will be truly awful. The camp is very silent and cheerless, signs that things are going awry."[194] "The weather was horrid, overcast, gloomy, snowy. One's spirits became very low."[195] "I expected these marches to be a little difficult, but not near so bad as to-day."[196] Indefinite conditions always tried Scott most: positive disasters put him into more cheerful spirits than most. In the big gale coming South when the ship nearly sank, and when we lost one of the cherished motors through the sea-ice, his was one of the few cheerful faces I saw. Even when the ship ran aground off Cape Evans he was not despondent. But this kind of thing irked him. Bowers wrote: "The unpleasant weather and bad surface, and Chinaman's indisposition, combined to make the outlook unpleasant, and on arrival [in camp] I was not surprised to find that Scott had a grievance. He felt that in arranging the consumption of forage his own unit had not been favoured with the same reduction as ours, in fact accused me of putting upon his three horses to save my own. We went through the weights in detail after our meal, and, after a certain amount of argument, decided to carry on as we were going. I can quite understand his feelings, and after our experience of last year a bad day like this makes him fear our beasts are going to fail us. The Talent [i.e. the doctors] examined Chinaman, who begins to show signs of wear. Poor ancient little beggar, he ought to be a pensioner instead of finishing his days on a job of this sort. Jehu looks pretty rocky too, but seeing that we did not expect him to reach the Glacier Tongue, and that he has now done more than 100 miles from Cape Evans, one really does not know what to expect of these creatures. Certainly Titus thinks, as he has always said, that they are the most unsuitable scrap-heap crowd of unfit creatures that could possibly be got together."[197]

"The weather was about as poisonous as one could wish; a fresh breeze and driving snow from the E. with an awful surface. The recently fallen snow thickly covered the ground with powdery stuff that the unfortunate ponies fairly wallowed in. If it was only ourselves to consider I should not mind a bit, but to see our best ponies being hit like this at the start is most distressing. A single march like that of last night must shorten their usefulness by days, and here we are a fortnight out, and barely one-third of the distance to the glacier covered, with every pony showing signs of wear. Victor looks a lean and lanky beast compared with his condition two weeks ago."[198]

But the ponies began to go better; and it was about this time that Jehu was styled the Barrier Wonder, and Chinaman the Thunderbolt. "Our four ponies have suffered most," writes Bowers. "I don't agree with Titus that it is best to march them right through without a lunch camp. They were undoubtedly pretty tired, and worst of all did not go their feeds properly. It was a fine warm morning for them (Nov. 13); +15°, our warmest temperature hitherto. In the afternoon it came on to snow in large flakes like one would get at home. I have never seen such snow down here before; it makes the surface very bad for the sledges. The ponies' manes and rugs were covered in little knots of ice."

The next march (November 13-14) was rather better, though the going was very deep and heavy, and all the ponies were showing signs of wear and tear. This was followed by a delightfully warm day, and all the animals were standing drowsily in the sunshine. We could see the land far away behind us, the first sight of land we had had for many days. On November 15 we reached One Ton Depôt, having travelled a hundred and thirty miles from Hut Point.

The two sledges left standing were still upright, and the tattered remains of a flag flapped over the main cairn. In a salt tin lashed to the bamboo flag-pole was a note from Lieutenant Evans to say that he had gone on with the motor party five days before, and would continue man-hauling to 80° 30´ S. and await us there. "He has done something over 30 miles in 2½ days—exceedingly good going."[199] We dug out the cairn, which we found just as we had left it except that there was a big tongue of drift, level with the top of the cairn to leeward, and running about 150 yards to N.E., showing that the prevailing wind here is S.W. Nine months before we had sprinkled some oats on the surface of the snow hoping to get a measurement of the accretion of snow during the winter. Unfortunately we were unable to find the oats again, but other evidence went to show that the snow deposit was very small. A minimum thermometer which was lashed with great care to a framework registered -73°. After the temperatures already experienced by us on the Barrier during the winter and spring this was surprisingly high, especially as our minimum temperatures were taken under the sledge, which means that the thermometer is shaded from radiation, while this thermometer at One Ton was left open to the sky. On the Winter Journey we found that a shaded thermometer registered -69° when an unshaded one registered -75°, a difference of 6°. All the provisions left here were found to be in excellent condition.

We then had a prolonged council of war. This meant that Scott called Bowers, and perhaps Oates, into our tent after supper was finished in the morning. Somehow these conferences were always rather serio-comic. On this occasion, as was usually the case, the question was ponies. It was decided to wait here one day and rest them, as there was ample food. The main discussion centred round the amount of forage to be taken on from here, while the state of the ponies, the amount they could pull and the distance they could go had to be taken into consideration.

"Oates thinks the ponies will get through, but that they have lost condition quicker than he expected. Considering his usually pessimistic attitude this must be thought a hopeful view. Personally I am much more hopeful. I think that a good many of the beasts are actually in better form than when they started, and that there is no need to be alarmed about the remainder, always excepting the weak ones which we have always regarded with doubt. Well, we must wait and see how things go."[200]

The decision made was to take just enough food to get the ponies to the glacier, allowing for the killing of some of them before that date. It was obvious that Jehu and Chinaman could not go very much farther, and it was also necessary that ponies should be killed in order to feed the dogs. The two dog-teams were carrying about a week's pony food, but they were unable to advance more than a fortnight from One Ton without killing ponies.

This decision practically meant that Scott abandoned the idea of taking ponies up the glacier. This was a great relief, for the crevassed state of the lower reaches of the glacier as described by Shackleton led us to believe that the attempt was suicidal. All the winter our brains were exercised to try and devise some method by which the ponies could be driven from behind, and by which the connection between pony and sledge could be loosed if the pony fell into a crevasse, but I confess that there seemed little chance of this happening. From all we saw of the glacier I am convinced that there is no reasonable chance of getting ponies up it, and that dogs could only be driven down it if the way up was most carefully surveyed and kept on the return. I am sure that in this kind of uncertainty the mental strain on the leader of a party is less than that on his men. The leader knows quite well what he thinks worth while risking or not: in this case Scott probably was always of the opinion that it would not be worth while taking ponies on to the glacier. The pony leaders, however, only knew that the possibility was ahead of them. I can remember now the relief with which we heard that it was not intended that Wilson should take Nobby, the fittest of our ponies, farther than the Gateway.

Up to now Christopher had lived up to his reputation, as the following extracts from Bowers' diary will show: "Three times we downed him, and he got up and threw us about, with all four of us hanging on like grim death. He nearly had me under him once; he seems fearfully strong, but it is a pity he wastes so much good energy.... Christopher, as usual, was strapped on three legs and then got down on his knees. He gets more cunning each time, and if he does not succeed in biting or kicking one of us before long it won't be his fault. He finds the soft snow does not hurt his knees like the sea-ice, and so plunges about on them ad lib. One's finnesko are so slippery that it is difficult to exert full strength on him, and to-day he bowled Oates over and got away altogether. Fortunately the lashing on his fourth leg held fast, and we were able to secure him when he rejoined the other animals. Finally he lay down, and thought he had defeated us, but we had the sledge connected up by that time, and as he got up we rushed him forward before he had time to kick over the traces.... Dimitri came and gave us a hand with Chris. Three of us hung on to him while the other two connected up the sledge. We had a struggle for over twenty minutes, and he managed to tread on me, but no damage done.... Got Chris in by a dodge. Titus did away with his back strap, and nearly had him away unaided before he realized that the hated sledge was fast to him. Unfortunately he started off just too soon, and bolted with only one trace fast. This pivoted him to starboard, and he charged the line. I expected a mix-up, but he stopped at the wall between Bones and Snatcher, and we cast off and cleared sledge before trying again. By laying the traces down the side of the sledge instead of ahead we got him off his guard again, and he was away before he knew what had occurred.... We had a bad time with Chris again. He remembered having been bluffed before, and could not be got near the sledge at all. Three times he broke away, but fortunately he always ran back among the other ponies, and not out on to the Barrier. Finally we had to down him, and he was so tired with his recent struggles that after one abortive attempt we got him fast and away."

Meanwhile it was not so much the difficulties of sledging as the depressing blank conditions in which our march was so often made, that gave us such troubles as we had. The routine of a tent makes a lot of difference. Scott's tent was a comfortable one to live in, and I was always glad when I was told to join it, and sorry to leave. He was himself extraordinarily quick, and no time was ever lost by his party in camping or breaking camp. He was most careful, some said over-careful but I do not think so, that everything should be neat and shipshape, and there was a recognized place for everything. On the Depôt Journey we were bidden to see that every particle of snow was beaten off our clothing and finnesko before entering the tent: if it was drifting we had to do this after entering and the snow was carefully cleared off the floor-cloth. Afterwards each tent was supplied with a small brush with which to perform this office. In addition to other obvious advantages this materially helped to keep clothing, finnesko, and sleeping-bags dry, and thus prolong the life of furs. "After all is said and done," said Wilson one day after supper, "the best sledger is the man who sees what has to be done, and does it—and says nothing about it." Scott agreed. And if you were "sledging with the Owner" you had to keep your eyes wide open for the little things which cropped up, and do them quickly, and say nothing about them. There is nothing so irritating as the man who is always coming in and informing all and sundry that he has repaired his sledge, or built a wall, or filled the cooker, or mended his socks.

I moved into Scott's tent for the first time in the middle of the Depôt Journey, and was enormously impressed by the comfort which a careful routine of this nature evoked. There was a homelike air about the tent at supper time, and, though a lunch camp in the middle of the night is always rather bleak, there was never anything slovenly. Another thing which struck me even more forcibly was the cooking. We were of course on just the same ration as the tent from which I had come. I was hungry and said so. "Bad cooking," said Wilson shortly; and so it was. For in two or three days the sharpest edge was off my hunger. Wilson and Scott had learned many a cooking tip in the past, and, instead of the same old meal day by day, the weekly ration was so manœuvred by a clever cook that it was seldom quite the same meal. Sometimes pemmican plain, or thicker pemmican with some arrowroot mixed with it: at others we surrendered a biscuit and a half apiece and had a dry hoosh, i.e. biscuit fried in pemmican with a little water added, and a good big cup of cocoa to follow. Dry hooshes also saved oil. There were cocoa and tea upon which to ring the changes, or better still 'teaco' which combined the stimulating qualities of tea with the food value of cocoa. Then much could be done with the dessert-spoonful of raisins which was our daily whack. They were good soaked in the tea, but best perhaps in with the biscuits and pemmican as a dry hoosh. "You are going far to earn my undying gratitude, Cherry," was a satisfied remark of Scott one evening when, having saved, unbeknownst to my companions, some of their daily ration of cocoa, arrowroot, sugar and raisins, I made a "chocolate hoosh." But I am afraid he had indigestion next morning. There were meals when we had interesting little talks, as when I find in my diary that: "we had a jolly lunch meal, discussing authors. Barrie, Galsworthy and others are personal friends of Scott. Some one told Max Beerbohm that he was like Captain Scott, and immediately, so Scott assured us, he grew a beard."

But about three weeks out the topics of conversation became threadbare. From then onwards it was often that whole days passed without conversation beyond the routine Camp ho! All ready? Pack up. Spell ho. The latter after some two hours' pulling. When man-hauling we used to start pulling immediately we had the tent down, the sledge packed and our harness over our bodies and ski on our feet. After about a quarter of an hour the effects of the marching would be felt in the warming of hands and feet and the consequent thawing of our mitts and finnesko. We then halted long enough for everybody to adjust their ski and clothing: then on, perhaps for two hours or more, before we halted again.

Since it had been decided to lighten the ponies' weights, we left at least 100 lbs. of pony forage behind when we started from One Ton on the night of November 16-17 on our first 13-mile march. This was a distinct saving, and instead of 695 lbs. each with which the six stronger ponies left Corner Camp, they now pulled only 625 lbs. Jehu had only 455 lbs. and Chinaman 448 lbs. The dog-teams had 860 lbs. of pony food between them, and according to plan the two teams were to carry 1570 lbs. from One Ton between them. These weights included the sledges, with straps and fittings, which weighed about 45 lbs.

Summer seemed long in coming for we marched into a considerable breeze and the temperature was -18°. Oates and Seaman Evans had quite a crop of frost-bites. I pointed out to Meares that his nose was gone; but he left it, saying that he had got tired of it, and it would thaw out by and by. The ponies were going better for their rest. The next day's march was over crusty snow with a layer of loose powdery snow at the top, and a temperature of -21° was chilly. Towards the end of it Scott got frightened that the ponies were not going as well as they should. Another council of war was held, and it was decided that an average of thirteen miles a day must be done at all costs, and that another sack of forage should be dumped here, putting the ponies on short rations later, if necessary. Oates agreed, but said the ponies were going better than he expected: that Jehu and Chinaman might go a week, and almost certainly would go three days. Bowers was always against this dumping. Meanwhile Scott wrote: "It's touch and go whether we scrape up to the glacier; meanwhile we get along somehow."[201]

Parhelia—E. A. Wilson, del.

As a result of one of Christopher's tantrums Bowers records that his sledge-meter was carried away this morning: "I took my sledge-meter into the tent after breakfast and rigged up a fancy lashing with raw hide thongs so as to give it the necessary play with security. A splendid parhelia exhibition was caused by the ice-crystals. Round the sun was a 22° halo [that is a halo 22° from the sun's image], with four mock suns in rainbow colours, and outside this another halo in complete rainbow colours. Above the sun were the arcs of two other circles touching these halos, and the arcs of the great all-round circle could be seen faintly on either side. Below was a dome-shaped glare of white which contained an exaggerated mock sun, which was as dazzling as the sun himself. Altogether a fine example of a pretty common phenomenon down here." And the next day: "We saw the party ahead in inverted mirage some distance above their heads."

In the next three marches we covered our daily 13 miles, for the most part without very great difficulty. But poor Jehu was in a bad way, stopping every few hundred yards. It was a funereal business for the leaders of these crock ponies; and at this stage of the journey Atkinson, Wright and Keohane had many more difficulties than most of us, and the success of their ponies was largely due to their patience and care. Incidentally big icicles formed upon the ponies' noses during the march and Chinaman used Wright's windproof blouse as a handkerchief. During the last of these marches, that is on the morning of November 21, we saw a massive cairn ahead, and found there the motor party, consisting of Lieutenant Evans, Day, Lashly and Hooper. The cairn was in 80° 32´, and under the name Mount Hooper formed our Upper Barrier Depôt. We left there three S (summit) rations, two cases of emergency biscuits and two cases of oil, which constituted three weekly food units for the three parties which were to advance from the bottom of the Beardmore Glacier. This food was to take them back from 80° 32´ to One Ton Camp. We all camped for the night 3 miles farther on: sixteen men, five tents, ten ponies, twenty-three dogs and thirteen sledges.

The man-hauling party had been waiting for six days; and, having expected us before, were getting anxious about us. They declared that they were very hungry, and Day, who was always long and thin, looked quite gaunt. Some spare biscuits which we gave them from our tent were carried off with gratitude. The rest of us who were driving dogs or leading ponies still found our Barrier ration satisfying.

We had now been out three weeks and had travelled 192 miles, and formed a very good idea as to what the ponies could do. The crocks had done wonderfully:—"We hope Jehu will last three days; he will then be finished in any case and fed to the dogs. It is amusing to see Meares looking eagerly for the chance of a feed for his animals; he has been expecting it daily. On the other hand, Atkinson and Oates are eager to get the poor animal beyond the point at which Shackleton killed his first beast. Reports on Chinaman are very favourable, and it really looks as though the ponies are going to do what is hoped of them."[202] From first to last Nobby, who was rescued from the floe, was the strongest pony we had, and was now drawing a heavier load than any other pony by 50 lbs. He was a well-shaped, contented kind of animal, misnamed a pony. Indeed several of our beasts were too large to fit this description. Christopher, of course, was wearing himself out quicker than most, but all of them had lost a lot of weight in spite of the fact that they had all the oats and oil-cake they could eat. Bowers writes of his pony:

"Victor, my pony, has taken to leading the line, like his opposite number last season. He is a steady goer, and as gentle as a dear old sheep. I can hardly realize the strenuous times I had with him only a month ago, when it took about four of us to get him harnessed to a sledge, and two of us every time with all our strength to keep him from bolting when in it. Even at the start of the journey he was as nearly unmanageable as any beast could be, and always liable to bolt from sheer excess of spirits. He is more sober now after three weeks of featureless Barrier, but I think I am more fond of him than ever. He has lost his rotundity, like all the other horses, and is a long-legged, angular beast, very ugly as horses go, but still I would not change him for any other."

The ponies were fed by their leaders at the lunch and supper halts, and by Oates and Bowers during the sleep halt about four hours before we marched. Several of them developed a troublesome habit of swinging their nosebags off, some as soon as they were put on, others in their anxiety to reach the corn still left uneaten in the bottom of the bag. We had to lash their bags on to their headstalls. "Victor got hold of his head rope yesterday, and devoured it: not because he is hungry, as he won't eat all his allowance even now."[203]

The original intention was that Day and Hooper should return from 80° 30´, but it was now decided that their unit of four should remain intact for a few days, and constitute a light man-hauling advance party to make the track.

The weather was much more pleasant and we saw the sun most days, while I note only one temperature below -20° since leaving One Ton. The ponies sank in a cruel distance some days, but we were certainly not overworking them and they had as much food as they could eat. We knew the grim part was to come, but we never realized how grim it was to be. From this Northern Barrier Depôt the ponies were mostly drawing less than 500 lbs. and we had hopes of getting through to the glacier without much difficulty. All depended on the weather, and just now it was glorious, and the ponies were going steadily together. Jehu, the crockiest of the crocks, was led back along the track and shot on the evening of November 24, having reached a point at least 15 miles beyond that where Shackleton shot his first pony. When it is considered that it was doubtful whether he could start at all this must be conceded to have been a triumph of horse-management in which both Oates and Atkinson shared, though neither so much as Jehu himself, for he must have had a good spirit to have dragged his poor body so far. "A year's care and good feeding, three weeks' work with good treatment, a reasonable load and a good ration, and then a painless end. If anybody can call that cruel I cannot either understand it or agree with them." Thus Bowers, who continues: "The midnight sun reflected from the snow has started to burn my face and lips. I smear them with hazeline before turning in, and find it a good thing. Wearing goggles has absolutely prevented any recurrence of snow-blindness. Captain Scott says they make me see everything through rose-coloured spectacles."

We said good-bye to Day and Hooper next morning, and they set their faces northwards and homewards.[204] Two-men parties on the Barrier are not much fun. Day had certainly done his best about the motors and they had helped us over a bad bit of initial surface. That night Scott wrote: "Only a few more marches to feel safe in getting to our goal."[205] At the lunch halt on November 26, in lat. 81° 35´, we left our Middle Barrier Depôt, containing one week's provisions for each returning unit as at Mount Hooper, a reduction of 200 lbs. in our weights. The march that day was very trying. "It is always rather dismal work walking over the great snow plain when sky and surface merge in one pall of dead whiteness, but it is cheering to be in such good company with everything going on steadily and well."[206]

There was no doubt that the animals were tiring, and "a tired animal makes a tired man, I find."[207] The next day (November 28) was no better: "the most dismal start imaginable. Thick as a hedge, snow falling and drifting with keen southerly wind."[208]

Bowers notes: "We have now run down a whole degree of latitude without a fine day, or anything but clouds, mist, and driving snow from the south." We certainly did have some difficult marches, one of the worst effects of which was that we knew we must be making a winding course and we had to pick up our depôts on the return somehow. Here is a typical bad morning from Bowers' diary:

"The first four miles of the march were utter misery for me, as Victor, either through lassitude or because he did not like having to plug into the wind, went as slow as a funeral horse. The light was so bad that wearing goggles was most necessary, and the driving snow filled them up as fast as you cleared them. I dropped a long way astern of the cavalcade, could hardly see them at times through the snow, but the fear that Victor, of all the beasts, should give out was like a nightmare. I have always been used to starting later than the others by a quarter of a mile, and catching them up. At the four-mile cairn I was about fed up to the neck with it, but I said very little as everybody was so disgusted with the weather and things in general that I saw that I was not the only one in tribulation. Victor turned up trumps after that. He stepped out and led the line in his old place, and at a good swinging pace considering the surface, my temper and spirits improving at every step. In the afternoon he went splendidly again, and finished up by rolling in the snow when I had taken his harness off, a thing he has not done for ten or twelve days. It certainly does not look like exhaustion!"

Indeed these days we were fighting for our marches, and Chinaman who was killed this night seemed well out of it. He reached a point less than 90 miles from the glacier, though this was small comfort to him.

Stumbling and groping our way along as we had been during the last blizzard we were totally unprepared for the sight which met us during our next march on November 29. The great ramp of mountains which ran to the west of us, and would soon bar our way to the South, partly cleared: and right on top of us it seemed were the triple peaks of Mount Markham. After some 300 miles of bleak, monotonous Barrier it was a wonderful sight indeed. We camped at night in latitude 82° 21´ S., four miles beyond Scott's previous Farthest South in 1902. Then they had the best of luck in clear fine weather, which Shackleton has also recorded at this stage of his southern journey.

It is curious to see how depressed all our diaries become when this bad weather obtained, and how quickly we must have cheered up whenever the sun came out. There is no doubt that a similar effect was produced upon the ponies. Truth to tell, the mental strain upon those responsible was very great in these early days, and there is little of outside interest to relieve the mind. The crystal surface which was an invisible carpet yesterday becomes a shining glorious sheet of many colours to-day: the irregularities which caused you so many falls are now quite clear and you step on or over them without a thought: and when there is added some of the most wonderful scenery in the world it is hard to recall in the enjoyment of the present how irritable and weary you felt only twenty hours ago. The whisper of the sledge, the hiss of the primus, the smell of the hoosh and the soft folds of your sleeping-bag: how jolly they can all be, and generally were.

(Nelson in The South Polar Times.)